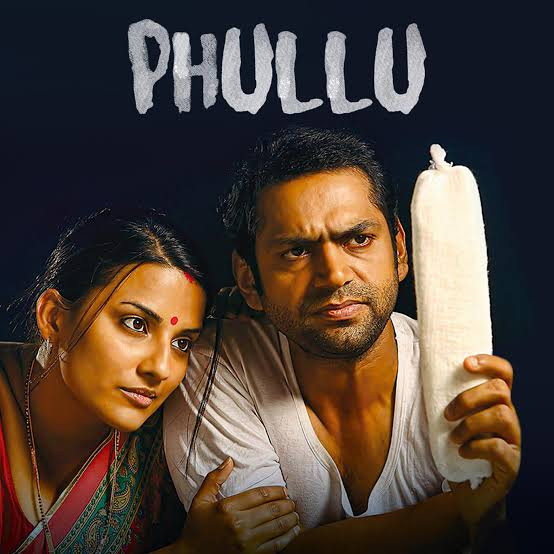

The ‘A’ Certificate For ‘Phullu’ Is Yet Another ‘F’ For The Government’s Judgment

In its wisdom, the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), Government of India, has deemed the Hindi film Phullu, fit only for ‘adult’ viewing because its story revolves around menstruation. The CBFC Chief, Pahlaj Nihalani, has defended this decision saying that young people in India aren’t ready yet to talk openly about ‘that time of the month’ leave alone watch a film about it.

Funny, tragic, outrageous, anachronistic. Add worse descriptors if you like, and they will fit. Even a couple of years ago, these responses would have sufficed, because underlying the outrage would be the hope that those in charge will learn the ropes and stop fooling around.

However, after three years in government, high officials should not expect any longer to be spoon-fed the basics of well-established feminist and freedom of expression arguments.

We

must recognise a pattern when it is staring us in the face. Please read the

CBFC’s ruling against Phullu in tandem with the outrageous (what else) recommendations

listed in the recently released booklet ‘Mother and Child Care’ by the Ayush

Ministry which tells pregnant women to avoid eating meat and not have sex.

Repeated instances of poor decisions by all manner of institutions

reveal a much deeper problem, which are way less joke worthy, and need serious

enquiry.

So what goes wrong with

a Pahlaj Nihalani? Why does he repeatedly need to be educated, why do his

attitudes need regular reconstruction?

Or what goes wrong with

a Yogi Adityanath when he does his flop show with the anti-romeo squad? Or the

Ayush Ministry with its rank outlandlish prescription for pregnant women?

Or for that matter, what

on earth went wrong with Narendra Modi himself, with the demonetisation

debacle, that is now deemed as a fruitless exercise even by BJP supporters? Or

the beef ban?

The influence of

regressive ideology, of which there is remarkable evidence - could partly

explain poor decisions. In May 2003, the

then Information and Broadcasting Minister Sushma Swaraj made the politically

pragmatic decision to impose a ban on condom advertising on

Doordarshan (India’s government founded public

service broadcaster). In

However, if we give the

government the benefit of doubt – discounting the possibility of any

unfortunate influence of ideology in all cases– we are left with two possible

reasons:

First - poor decisions and

bad judgement can be put down to sheer lack of capacity to rationally process

evidence, which it may well be.

But let us not forget,

that the Indian governance system, circuitous though it may be, is designed to

factor in individual variations in capacity, by encumbering due process with

multiple layers of consultation and approvals. This minimises the influence of

any single individual’s poor capacity on critical decisions that have the

potential to influence large numbers of people’s lives.

Second - if despite

these checks and balances, there is a deluge of poor decisions, the malaise

points to a worse diagnosis than the innocent one of lack of capacity.

We may be witnessing a

new norm -the rise of the powerful, autocratic, whimsical lone decision maker with

an infantile delusion of greatness and an incurable degree of deafness for good

advice. Much like the lone wolf attackers.

Visualize for a moment

that such a person was the pilot of your aircraft. No don’t, it seems

catastrophic even in imagination.

Coming back to the

flavour of the day, Pahlaj Nihalani – would he have made a more respectable

decision and not given an ‘adult’ certificate to Phullu had he been aware of,

or provided with, the following three data points?

National Family Heath Survey

reports, for example, that 39% women and 40% men in Bihar reported underage

marriage, and in Andhra Pradesh, a state with better development indices,

nearly 33% women and 24% men reported underage marriage. In all, nearly 12

million Indian children were married before the age of 10 years (Census of

India 2011).

Marriage

aside, leading newspapers reported in 2015 that according to a survey, urban

youth have their ‘first

brush’ with sex at 14.

In

a 2014 survey in Delhi by the government run Safdarjung Hospital, more than

80% of the parents interviewed insisted that sexuality

education be provided in schools and in fact be made compulsory.

Therefore, CBFC may try as it will, viewers below the age of 18, who will not be allowed to watch this film, are accessing information on sex and sexuality from cousins, friends, aunts and of course, on the internet.

And they usually get the wrong information, leading to an array of problems including unwanted pregnancies, and even suicides.

Poor decisions by some people in power can play out with blood in the backyards of many. Remember the pilot who flew a plane full of children into the Alps, killing everyone?

Youth-friendly health services and service providers, and measures such as comprehensive sexuality education are almost missing in India. According to a recent UNFPA report, this has a direct negative impact on the prospects of reaping demographic dividend that India so desperately seeks.

Every young girl and boy, anywhere in the world, and in India, happens to have a right to know about important matters like menstruation and allied matters such as sex and sexuality, despite our collective squeamishness in this regard.

Can the CBFC please do some homework, nominate a few young people, maybe some experts on adolescent health, and make their decision making process more fool-proof, please?

https://www.huffpost.com/archive/in/entry/the-a-certificate-for-phullu-is-yet-another-f-for-the-gove_in_5c11fa26e4b0295df1fa99da

Comments